Audio Sample

Thomson Smillie

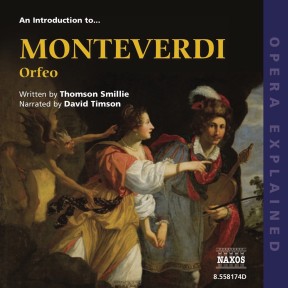

Opera Explained – Orfeo

Read by David Timson

unabridged

Monteverdi’s Orfeo, first performed in 1607, generates a special excitement because it is the first unquestioned masterpiece of opera. Notable for its precise orchestration and powerful drama it was a groundbreaking work. It concerns the legend of Orpheus, the demi-god whose music had the power to conquer the forces of Hell and to bring his wife back, briefly, to life. The extracts used in this introduction are from Naxos’s full recording; it uses authentic period instruments, which serve to evoke the early Baroque period of the opera’s composition.

-

1 CDs

Running Time: 1 h 17 m

More product details

ISBN: 978-1-84379-101-0 Digital ISBN: 978-1-84379-331-1 Cat. no.: NA558174 Download size: 36 MB BISAC: MUS028000 Released: November 2008 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Booklet Notes

The word ‘opera’ is Latin and means ‘the works’; it represents a synthesis of all the other arts: drama, vocal and orchestral music, dance, light and design. Consequently, it delivers an emotional impact which none of the others can match. The only one of the arts whose origins can be precisely dated, it was ‘invented’ in Italy in 1597 as part of the Renaissance – the rebirth of interest in classical values. As an art form it is truly international, crossing all linguistic and cultural barriers, and it is probably the only one whose audience continues to expand, not in spite of but because of developments in entertainment technology.

From its early origins in Italy opera spread across Europe, establishing individual and distinctive schools in a number of countries. France had an early and longstanding love affair with it – hence the term grand opéra, referring to the massive five-act creations that graced the Paris Opéra in the nineteenth century. Germany had an excellent school from as early as Mozart’s time, and opera perhaps reached its highest achievement with the mighty music dramas of Richard Wagner. Russia, Great Britain and the Americas have also made their contributions.

In the popular imagination, however, opera remains an Italian concept – and no wonder. From its earliest years it was dominated by the Italians: Cavalli and Monteverdi were among the first to establish its forms; there was a golden age, called the bel canto, at the beginning of the nineteenth century when Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini ruled supreme; Giuseppe Verdi was probably the most revered artist in musical history; and, for many, Puccini represents in every sense the last word in this beloved genre.

Although the twentieth century has not been as lavishly endowed with opera composers, it can still boast a few, including Richard Strauss, Igor Stravinsky and Benjamin Britten – and, maybe most significantly in the long run, those errant stepchildren of opera, the Broadway musical and the Lloyd Webber spectacular.

Orfeo

Music fable in a prologue and five acts by Claudio Monteverdi.

Libretto by Alessandro Striggio (c. 1573–1630).

First performance: Mantua carnival, 24 February 1607.

First UK performance: London, 8 March 1924 (concert performance).

First US performance: New York, 14 April 1912.

Monteverdi’s retelling of the story of Orpheus was not the very first opera ever written during the intellectual and cultural ferment that was the Late Renaissance, but it is the first unquestioned masterpiece and set the operatic tone and the style for decades to come. The first ostensible opera, Dafne, was written by Jacopo Peri in 1597, but has been lost.

Though Monteverdi was no musical innovator, his Orfeo is the first great opera that survives. He was a skilled composer of madrigals, and many of the forms and harmonic devices he employs in Orfeo would already have been familiar to his audiences. However, by imposing form and structure to the often rambling business of early opera, he ensued that ‘plays with music’ – as operas were generally called in the early days – would provide the basis of Italian musical life for four centuries.

Monteverdi was born in the Lombard town of Cremona in 1567, and lived to the then grand old age of 76. From Cremona – home, incidentally, of a school of great violin makers that would include Stradivari – Monteverdi made his way to the ducal court of Mantua, where he was employed in the court of the Gonzaga family. He married but was widowed tragically young and soon left for Venice, where he spent the later and greater part of his life. He wrote a number of operas, three of which guarantee him an honoured place among the great composers. These are: Orfeo, The Return of Ulysses and The Coronation of Poppea.

It is easy to see why the Greek legend of Orpheus has attracted composers: it flatters their profession. Orpheus was a demi-god, offspring of the god Apollo, and was endowed with remarkable musical skills that charmed the people, birds, animals and hills of Ancient Greece. He married the lovely Eurydice, and much of the earlier part of Orfeo is concerned with extolling her beauty and her charms. But tragically, Eurydice was bitten by a snake while walking in the Fields of Thrace, where the opera opens. She died and descended into hell. Orpheus followed her, and with the power of his music was able to charm the gods of the underworld into letting him bring her up into the living world. But there was one condition: that he may not look back at her. He did turn, of course, and Eurydice was then lost to him forever. That, at least, is what happens in the classical legend, though there are several available endings. In the original, Orpheus is ripped to pieces by a crowd of shrieking women. In Gluck’s opera Orpheus ed Eurydice, the god of love arranges a reprieve and the lovers are united. In one of the two available endings to Monteverdi’s opera, the god Apollo descends on a cloud and takes his son up to heaven where he may admire his wife among the constellations. This recording gives us two endings: the screaming women and the flying Apollo.

It is fascinating how respect for the performing traditions of early music has grown over the last few decades since the revival of interest in Monteverdi’s operas truly got under way. In accordance with now accepted practice, we shall hear singers perform in what is believed to be the correct vocal ranges – counter-tenors, for example, replacing castrati. Equally importantly, the orchestral musicians play original period instruments (or copies) in order to create something approximating the sound of a distant age.

Synopsis

Prologue

La Musica greets the spectators, announces the subject matter of the drama and tells of the wonderful effect that the art of music has on the human spirit.

Act I

In the fields of Thrace. Orpheus is to marry Eurydice, and nymphs and shepherds are celebrating the happy day.

Act II

In the woods. Eurydice and her attendants leave, and Orpheus sings of his joy. His happiness is short-lived, for Sylvia, a messenger, arrives and announces that Eurydice has been bitten by a snake and has died. Orpheus is shattered and laments his bride, but then he resolves to descend into Hades and recover Eurydice.

Act III

In the underworld. Orpheus descends accompanied and comforted by Hope as far as the gates of Hades. He reaches the Styx, but the boatman, Charon, will not allow him to pass. Orpheus summons up all the florid and magical charms of music, but Charon remains unmoved. Spurred on by his need to find Eurydice, Orpheus devises a new plan and lulls Charon to sleep. He then rows himself across while the chorus sings of man’s power to overcome obstacles.

Act IV

In the underworld. Pluto, king of the underworld, and his wife Proserpine have heard Orpheus’ lament. Proserpine is moved to plead on behalf of Orpheus, and Pluto agrees that Eurydice can return to earth. However, he stipulates that under no circumstances must Orpheus look back at Eurydice as he leads her from the underworld. The chorus sings that even in Hades there is such a thing as mercy. Orpheus joyfully sings in praise of his lyre while he leads Eurydice earthwards. But then he has his doubts, and turns to see if she is really following him. As he does so, she disappears before his eyes. Orpheus returns to earth alone, while the chorus remarks on the paradox of being able to conquer Hades but not one’s own will.

Act V

In the fields of Thrace. Lamenting his loss of Eurydice for the second time, the distraught Orpheus responds by renouncing women. However, at this moment, Apollo, Orpheus’ father, appears from the heavens in his chariot. He consoles his son with the promise of immortality and says he will forever see Eurydice in the stars. Apollo and his son then ascend to heaven while the chorus rejoices in Orpheus’ apotheosis.

Notes by Thomson Smillie