Audio Sample

Jeremy Siepmann

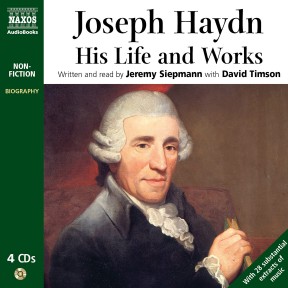

Joseph Haydn: His Life and Works

Read by Jeremy Siepmann with David Timson

unabridged

Symphonies, quartets, concertos and keyboard works poured from the pen of Joseph Haydn, making him one of the most important figures in classical music. Jeremy Siepmann tells the story of the man and his work in this lively autobiography, enhanced by numerous examples of the music itself, taken from the Naxos catalogue. There is no better programme with which to mark the 200th anniversary of the composer’s death.

-

4 CDs

Running Time: 4 h 40 m

More product details

ISBN: 978-962-634-951-9 Digital ISBN: 978-962-954-843-8 Cat. no.: NA495112 Download size: 130 MB BISAC: BIO004000 Released: March 2009 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Buy on CD at Downpour.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Reviews

Taken from humble parents to be a choirboy, six-year-old Haydn endured hunger and harshness, but finally became the “father” of the symphony and the string quartet. Exiled for years in the isolation of the Esterházys’ Hungarian palace, he finally saw London – and the sea – at 60. Delightfully illustrated with generous musical pieces.

Rachel Redford, Observer

Booklet Notes

Few, if any, composers in history have sparked more affection than Joseph Haydn: as man, musician, administrator, unofficial diplomat, inspired creator and master craftsman, he personified the best in humanity. No man is faultless, but Haydn might be said to have possessed more than the normal share of virtues. In his warmth, generosity and humility, with his humour, his total lack of malice and his transparent honesty, he endeared himself to audiences and musicians wherever he went. That he was also a genius of towering stature, comparable in his time only with Mozart and Beethoven (both of them infinitely more complex individuals and both, in their different ways, his pupils), makes this catalogue of blessings all the more remarkable. Of all creative geniuses, in any field, none is more notable than Haydn for his abundant and invigorating good health. As a composer, he was without neurosis. And though he need bow to no-one in sophistication, there is a directness of utterance in his music that constantly includes the listener. More often than not he is talking to us rather than addressing us. But he never talks down to us. He keeps us on our toes, wondering, guessing at what comes next, delighting in his endless invention. His music invites us into his mind – and what a mind! When we listen to Haydn we can hear musical thought in action, and with exceptional clarity. Yet the music is never conspicuously, let alone primarily, intellectual. Haydn the musician is an intellectual, but he speaks both from and of the heart. All in all, he was one of nature’s great originals.

Born in 1732, to a wheelwright and a cook, he was not particularly well educated and was even something of a slow developer in music. Nor did he ever compose with the quicksilver fluency of a Mozart or a Mendelssohn. He entered the profession not by inheritance but almost by default. Yet where music is concerned, this cheerful country bumpkin, with his lifelong penchant for jokes, was very largely to shape an age, and herald another. In addition to the fond and ubiquitous nickname ‘Papa’ Haydn, paternal attributes clustered around him. He is known to this day as ‘the father of the symphony’, ‘the father of the string quartet’ and ‘the father of the Classical sonata’. These are all over-simplifications – musical evolution is not as neat as human genealogy – but they are essentially justified. And in the process of fathering an era he wrote some of the richest and most profound music ever conceived. Much of this sprang from his inner life; but much, too, reflected the major changes taking place in the society around him.

The music of the Classical era (c. 1750–1830) was based on preconceived notions of order, proportion and grace. Predominant were beauty and symmetry of form, which combined to create an effectively Utopian image, an idealisation of universal experience. In the Romantic age (which Haydn anticipated, and which his pupil Beethoven came close to defining in his own revolutionary output), from the early 1800s onwards, this was gradually replaced by a cult of individual expression, the crystalisation of the experience of the moment, the unfettered confession of powerful emotions and primal urges, the glorification of sensuality, a flirtation with the supernatural, an emphasis on spontaneity and improvisation, and the cultivation of extremes – emotional, sensual, spiritual and structural. Where a near-reverence for symmetry had characterised the Classical era, Romanticism delighted in asymmetry (a feature discreetly but significantly anticipated by Haydn). Form was not a receptacle but a by-product of emotion, to be generated from within. While the great Romantic painters covered their canvases with grandiose landscapes, the great Romantic composers (starting with Beethoven and Weber but foreshadowed by Haydn, particularly in his two late oratorios The Creation and The Seasons) attempted similar representations in sound. In its cultivation and transformations of folk music (or that which was mistakenly perceived as such), music became an agent of nationalism, one of the most powerful engines of the Romantic era. In Haydn, this is reflected in the deliberately ‘Hungarian’ references that crop up in a number of his later works, such as the D major Piano Concerto and the late G major Piano Trio, with its famous ‘Gypsy’ Rondo. It was a trend directly connected to politics.

Inevitably, the ideals and consequences of the French Revolution were a source of great alarm to the rulers of the crumbling Holy Roman Empire. As a consequence, Austria, with Vienna as its capital, became a both a bastion against French imperialism and an efficient police state, in which liberalism, both political and philosophical, was ruthlessly suppressed. But the people of Vienna were not natural revolutionaries, and neither was Haydn. Indeed the Viennese were noted for their political apathy. Exceptions to this were during the two occupations by the French in 1805 and 1809 (the year of Haydn’s death), which brought considerable hardship to the city in the form of monetary crises, serious food shortages and a fleeing population, while Austria as a whole suffered serious political and territorial setbacks.

With the final defeat of Napoleon, however, Austria became the principal focal point of European diplomatic, commercial and cultural life. To an unprecedented degree, music everywhere passed out of the palaces and into the marketplace – a transition in which Haydn and his works played a significant part (most notably in Paris and London). Composers were decreasingly dependent on aristocratic patronage (Haydn had spent most of his life in a servant’s livery), now relying for their livelihood on the sales of their work – or, more commonly, on their income as teachers. Vienna then housed something in excess of 6,000 piano students – most of whom will have cut their teeth, as it were, on the sonatas of Haydn. These range from the lightweight, rather Scarlattian style of his early ones to the almost Beethovenian power, substance and grandeur of the final sonata in E flat (1794). Yet in the realm of the public concert, which Haydn did so much to nourish, Austria lagged well behind England. It was not until 1831, twenty-two years after Haydn’s death, that Vienna acquired its own purpose-built concert hall. Fortunately, Haydn’s works had long since been rendered immortal.

Notes by Jeremy Siepmann