Audio Sample

Thomson Smillie

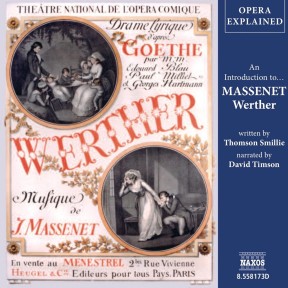

Opera Explained – Werther

Read by David Timson

unabridged

Massenet’s Werther combines a deeply tender story with music of beauty and eloquence. One act alone contains two of the greatest arias in the repertoire: the mezzo-soprano aria ‘Va! Laisse couler mes larmes’ and the tenor’s ‘Pourquoi me rèveiller’. In their sentimental power and melodic richness these arias encapsulate the qualities that account for the universal popularity of this great work.

-

1 CDs

Running Time: 1 h 19 m

More product details

ISBN: 978-1-84379-100-3 Digital ISBN: 978-1-84379-330-4 Cat. no.: NA558173 Download size: 37 MB Produced by: Genevieve Helsby Edited by: Sarah Butcher BISAC: MUS028000 Released: July 2005 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Buy on CD at Downpour.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Booklet Notes

The word ‘opera’ is Latin and means ‘the works’; it represents a synthesis of all the other arts: drama, vocal and orchestral music, dance, light and design. Consequently, it delivers an emotional impact which none of the others can match. The only one of the arts whose origins can be precisely dated, it was ‘invented’ in Italy in 1597 as part of the Renaissance – the rebirth of interest in classical values. As an art form it is truly international, crossing all linguistic and cultural barriers, and it is probably the only one whose audience continues to expand, not in spite of, but because of developments in entertainment technology.

From its early origins in Italy opera spread across Europe, establishing individual and distinctive schools in a number of countries. France had an early and long- standing love affair with it – hence the term grand opéra, referring to the massive five-act creations that graced the Paris Opéra in the nineteenth century. Germany had an excellent school from as early as Mozart’s time, and opera perhaps reached its highest achievement with the mighty music dramas of Richard Wagner. Russia, Great Britain and the Americas have also made their contributions.

In the popular imagination, however, opera remains an Italian concept – and no wonder. From its earliest years it was dominated by the Italians: Cavalli and Monteverdi were among the first to establish its forms; there was a golden age, called the bel canto, at the beginning of the nineteenth century when Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini ruled supreme; Giuseppe Verdi was probably the most revered artist in musical history; and, for many, Puccini represents in every sense the last word in this beloved genre.

Although the twentieth century has not been as lavishly endowed with opera composers, it can still boast a few, including Richard Strauss, Igor Stravinsky and Benjamin Britten – and, maybe most significantly in the long run, those errant step- children of opera, the Broadway musical and the Lloyd Webber spectacular.

Werther

Drame lyrique in four acts by Jules Massenet. Libretto by Edouard Blau, Paul Milliet and Georges Hartmann, based on Die Leiden des jungen Werthers by Goethe. First performance: Vienna, Hofoper, 16 February 1892. First UK performance: London, Covent Garden, 11 June 1894. First US performance: Chicago, 29 April 1894.

While the image of the artist starving in a garret is a popular one with opera composers, few of them actually suffered the fate themselves. Mozart and Wagner occasionally did, but not Rossini, Massenet or Puccini, all of whom became very rich through the composition of their operas. This was true especially of Massenet, the dominant figure of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century French opera. He wrote around twenty-five operas, of which Manon and Werther remain firmly in the repertory, and others like Thaïs and Hérodiade are on the fringes. He was a meticulous, businesslike and punctual composer who turned out one perfumed masterpiece after another to delight the international audiences of the belle époque. He had a sure sense of theatre and craftsmanship which combined with a gift for melody and orchestration to ensure his enduring success.

Werther is regarded by many as Massenet’s masterpiece. The source of the plot is a novel, usually translated as The Sorrows of Young Werther, by the great German Romantic poet Goethe. It involves the unrequited love of an ardent young man for the lovely Charlotte. She is pledged to marry another, and when she does so Werther, after much anguishing, commits suicide. So great was the impact of this novel on early nineteenth-century sensibilities that the work was banned by church authorities – suicide was seen as the ultimate blasphemy, showing a lack of faith in God’s purpose – yet fashionably depressed young men were known to have taken their lives in imitation of its hero.

The attractions of Massenet’s work are not difficult to appreciate. The story is straightforward and deeply touching, and as it combines rustic simplicity – the home life of Charlotte, her sister Sophie and her father – with grand passion and internal anguish, it offers excellent opportunities for rich characterisation and melodic invention. In fusing affecting melody with vivid orchestration, Massenet excels. Jealous musicians are much given to coining insulting nicknames for their more successful colleagues, and Massenet himself was labelled with two. An early incident in this opera introduces us to a musical theme which will characterise the love of Werther for Charlotte and is of such tender beauty that Massenet’s nickname ‘Gounod’s son’ seems understandable. It is later developed into an orchestral passage of such power that the origins of the second and more insulting of the nicknames, ‘Wagner’s daughter’, also become apparent.

Act Three includes one scene and two arias, all of which are among the most treasured of operatic numbers. The Letter Scene is a pillar of the mezzo-soprano repertoire and Charlotte’s aria ‘Va! Laisse couler mes larmes’ is among the most tender and beautiful creations in French opera. But it is the tenor aria ‘Pourquoi me réveiller’, with its wistfulness for the solace of death, that lives longest in the memory.

Of course the very qualities of the perfumed and the sensuous which make Massenet such a favourite with audiences have led occasionally to his being disparaged by sterner souls; but happily the opera Werther has attracted almost universal admiration, possibly because the literary underpinnings are so deep and the musical expression so obviously and sincerely felt as to disarm even the most cynical non-romantic. For the rest of us it is a work of irresistible melodic beauty, and one of the most enjoyable French operas from what is now seen as a golden age of music theatre.

Synopsis

The action takes place in Wetzlar near Frankfurt in 1780.

Act I In the garden of the Bailli (magistrate). The Bailli is teaching his children a Christmas carol. His friends Johann and Schmidt call to invite him out to the inn later, to discuss the evening’s ball and, in particular, his eldest daughter Charlotte’s partner for the occasion – the poet Werther. They also ask about the return of Albert, Charlotte’s fiancé. They leave, and Charlotte tends to the children as Werther arrives and looks on admiringly at the domestic scene. Having entrusted the care of the children to her younger sister Sophie, Charlotte leaves with Werther, and the Bailli goes to join his friends at the inn, encouraged by Sophie. Albert returns unexpectedly and is disappointed not to find Charlotte. Sophie reassures him that Charlotte has not forgotten him. When Charlotte and Werther are returning from the ball, Werther declares his love for her. He asks if they may meet again, and the Bailli’s voice is heard proclaiming Albert’s return. Charlotte tells Werther that this is the man she promised her dying mother that she would marry.

Act II

The square at Wetzlar. It is a holiday, and people are celebrating the golden wedding of the Pastor. Among them are Charlotte and Albert, having been married for three months. Johann and Schmidt toast the young couple, and Werther watches from a distance, regretful. Albert comes and speaks to him, telling Werther of his happiness and sympathising with Werther’s regret at not having Charlotte for himself. Werther decides to talk to Charlotte, but she begs him to keep his distance, at least until Christmas. Sophie asks him to dance, but he violently refuses, which upsets her. He tells her he is leaving forever. She repeats this to Charlotte, and by her reaction Albert knows that Charlotte loves Werther.

Act III

A room in Albert’s house, on Christmas Eve. Charlotte re-reads letters from Werther that she should have destroyed. She cannot disguise from Sophie that she is bitterly unhappy. Werther appears, pale and distraught, at the window. Charlotte weeps as he recites some lines of Ossian, and when he begs her for a kiss her resolve fails. She soon recovers herself and leaves the room, swearing never to see him again. He is shattered and rushes away. Albert arrives and suspects that Werther has been there. A servant enters with a request from Werther to borrow Albert’s pistols for a long journey. Albert coldly instructs his wife to hand them over. Once alone, Charlotte rushes out, praying that she won’t be too late.

Act IV

Werther’s study. Charlotte finds Werther lying on the floor, mortally wounded. He prevents her from fetching help. Charlotte confesses that she has loved him since their first meeting. Werther dies in her arms, and in the distance children are heard singing the Christmas carol.

Notes by Thomson Smillie