Audio Sample

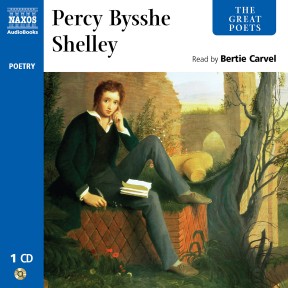

Percy Bysshe Shelley

The Great Poets – Percy Bysshe Shelley

Read by Bertie Carvel

selections

Idealist, atheist, outcast, political radical and, of course, poet – Percy Bysshe Shelley was, in many ways, the epitome of the Romantic artist. His poetry was an outlet for his passionately-held and highly unpopular beliefs; beliefs which resulted in social exclusion, exile, and possibly even his premature death at the age of twenty-nine. His work is a monument to his convictions and to the power of the human spirit, and today it is recognised as a key contribution to Romantic literature. This anthology contains many of his best-known poems, including Ozymandias, The Mask of Anarchy and To a Skylark, as well as excerpts from (among others) Prometheus Unbound and Adonaïs, all read by Bertie Carvel, one of the most talented English actors of his generation.

-

1 CDs

Running Time: 1 h 18 m

More product details

ISBN: 978-962-634-861-1 Digital ISBN: 978-962-954-672-4 Cat. no.: NA186112 Download size: 19 MB BISAC: POE005020 Released: March 2008 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Buy on CD at Downpour.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Included in this title

- The opening lines from Queen Mab: A Philosophical Poem

- Mutability

- To Wordsworth

- Hymn to Intellectual Beauty

- Ozymandias

- Stanzas Written In Dejection Near Naples

- from ‘Prometheus Unbound’

- The Indian Serenade

- Ode to the West Wind

- Song to The Men of England

- Sonnet: England in 1819

- The Mask of Anarchy

- The Cloud

- To A Skylark

- from Epipsychidion

- To the Moon

- A Lament

- One word is too often profaned

- Chorus from Hellas

- Concluding stanzas from Adonais

- With A Guitar, To Jane

- Song: Rarely, rarely, comest thou

- To Jane: The Invitation

- Time

- Lines: ‘When the lamp is shattered’

- Music, When Soft Voices Die

- To Jane: The Recollection

Booklet Notes

The period into which Shelley was born in 1792 was witness to some of the most wide-ranging and abrupt transformations in the history of European civilisation.

Shelley’s response to these upheavals was complex but robust, and highly individual, not to say courageous. His outspoken views began to get him in trouble from the very beginning, even while a scholar at Eton, where he was the victim of bullying both for his atheism and his refusal to ‘fag’ for an elder boy, let alone for his apparently somewhat epicene appearance.

At Oxford he published a Gothic novel, Zastrozzi, and, with his sister Elizabeth, Original Poetry by Victor and Cazire. Interestingly, another publication (written in collaboration with Thomas Jefferson Hogg, his closest friend at Oxford), which came before the public under the title of Posthumous Fragments of Margaret Nicholson, being poems found among the papers of that noted female who attempted the life of the king in 1796, is a clear expression of his republicanism.

Dangerously subversive though these verses might have been, it was his much more directly challenging pamphlet The Necessity of Atheism, also written with Hogg, which led him to be rusticated and – when his father failed to persuade him to recant – sent down in disgrace.

Such, or similar, views must surely have been expressed by other students in previous decades, and even concurrently with the effusions of Shelley and Hogg, but the difference with Shelley was that rather than simply ‘letting off steam’ before ‘knuckling under’ and ultimately fitting in, he meant what he said and stood by it.

His refusal to submit to paternal and academic authority is all one with his youthful idealism, but it led to a complete break with his family. Had he been able to compromise, he would in time have inherited his father’s baronetcy and become a Member of Parliament, but it is hard to imagine the author of The Mask [masque] of Anarchy meekly taking his place in the Lords and declining into a settled existence with wife and children.

The breach with his father was made worse when Shelley eloped to Scotland with the beautiful sixteen-year-old Harriet Westbrook, who had earlier broken off their correspondence in shock at his irreligious views. Shelley’s allowance was cut off, resulting in persistent money problems, even though a partial restoration was negotiated.

From Scotland the young couple moved to the Lake District – after Shelley had failed to persuade his wife to accept sharing lodgings with his friend Hogg and his wife. Already shocked by her husband’s apostasy, Harriet rejected any idea of an open marriage.

During a visit to Ireland he engaged in radical pamphleteering, wrote the Address to the Irish People, and attended nationalist rallies. Not content with this, he authored A Declaration of Rights on the subject of the French revolution, but it was deemed too radical for distribution in Britain.

At Lynmouth in Devon he set about establishing a small commune of like-minded idealists, but moved to Wales on learning that because of his radical activities and writings he was coming under the baleful eye of Home Office agents. There is even a story that a shepherd fired three shots at him while he was living in Tanyrallt in Carnarvonshire.

In 1813 he published his first major poem, Queen Mab, later to become known as ‘the Chartist’s Bible’. In the prose notes Shelley covers free love, atheism, Christianity and vegetarianism.

Shelley began leaving Harriet alone with their baby daughter Ianthe to spend time in London, particularly at the bookshop and home of the freethinker William Godwin, who had formed a liaison with the very forward-looking proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women. When she had become pregnant they had married, but Mary later died giving birth to a daughter, whom the broken-hearted William named after his wife.

In 1814 Shelley abandoned Harriet, now pregnant with their second child, to elope with another sixteen-year-old – the daughter of his mentor. Mary, Shelley’s intellectual equal, was altogether a more suitable partner. Together with Mary’s step-sister Claire Clairmont, also sixteen, they sailed to Europe, crossing France and settling in Switzerland, of which journey the Shelleys later published an account.

The continental venture ended bathetically, as they had to return to England, depressed, homesick and without funds. To their consternation Godwin, the one-time advocate of free love, refused to see his daughter and her lover.

In 1815 Shelley produced Alastor; or, The Spirit of Solitude, now recognised as one of his more important early pieces.

Lured back to Switzerland by Claire (who had begun an affair with Lord Byron, although Byron was tiring of her), Shelley and Mary settled in a neighbouring house, and during this time both poets influenced each other’s work. Shelley’s Hymn to Intellectual Beauty dates from this period.

Back again in England in 1815, they were relieved of financial difficulties by the death of Shelley’s grandfather and a subsequent inheritance, but both Mary’s half-sister Fanny and, later, Shelley’s estranged wife Harriet committed suicide. Mary became Shelley’s second wife at the end of that year.

Living for a while in Buckinghamshire, Shelley became part of a circle that included Thomas Love Peacock and Leigh Hunt and it was at this time that he also met John Keats (memorialised in his fine, moving Adonaïs).

In 1818 the Shelleys left England for good after the long poem Laon & Cythna – its subject matter incest and attacks on religion – had to be withdrawn from publication (it later appeared in edited form as The Revolt of Islam). The ostensible purpose of the move was to escort Claire and her daughter Allegra on their way to see Allegra’s father, Byron.

For the next four years the Shelleys moved from city to city in Italy, Shelley writing copiously and powerfully, producing, on the one hand, extensive verse dramas such as Prometheus Unbound and, on the other, intimate addresses to another object of love and desire, Jane Williams, the common law wife of a member of his circle.

Shelley’s death in 1822 by drowning as the result of a sailing incident has never been satisfactorily explained. Although he was no expert sailor, evidence suggests that it was through no fault of his own that his schooner, the Don Juan, capsized. One theory is that he was effectively murdered, maybe by agents of the British government.

Shelley is the paradigm of the youthfully idealistic poet, but to dismiss him as T. S. Eliot once did as an ‘adolescent’ seems to suggest that Shelley ought to have ‘grown up’ and been content to partake of the hidebound conventionality, corruption and hypocrisies of Regency England. It is hard to believe that had Shelley lived on, his life would have traced a pattern comparable to Wordsworth’s. His early death seems an essential part not only of the myth of the doomed poet, but also of the spirit of this particular poet himself: that it is preferable to die young than disillusioned, but also that man is at his best when he yearns, hopes, dreams and stretches out his hand towards the ideal, ever striving for a better world.

Maurice West