Audio Sample

John Donne

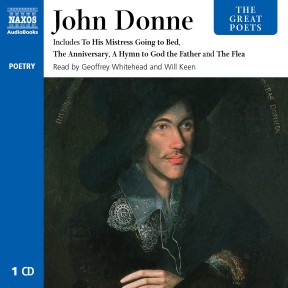

The Great Poets – John Donne

Read by Geoffrey Whitehead & Will Keen

selections

Sophisticated wit and intense emotion, religious fervour and erotic sensuality, delight in life’s pleasures and fascination with death, are all to be found in the paradoxical poetry of John Donne. One of the foremost metaphysical poets, Donne’s ingenious metaphors and inspired use of language has earned him affection and reverence in near equal measure to Shakespeare. This collection of his finest poetry showcases the diverse range of his work, and includes Death Be Not Proud, A Hymn to God the Father, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Go Catch a Falling Star, The Flea and To His Mistress Going to Bed.

-

1 CDs

Running Time: 1 h 10 m

More product details

ISBN: 978-1-84379-357-1 Digital ISBN: 978-962-954-964-0 Cat. no.: NA135712 Download size: 17 MB BISAC: POE005020 Released: June 2010 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Included in this title

- The Anniversary

- A Valediction Forbidding Mourning

- Holy Sonnet – Batter my heart, three person’d god

- The Sun Rising

- Elegy – On His Mistress

- The Bait

- Elegy – To His Mistress Going to Bed

- Holy Sonnet – Death, be not proud

- The Canonisation

- The Computation

- Song – Go and catch a falling star

- Holy Sonnet – I am a little world made cunningly

- The Triple Fool

- The Indifferent

- Witchcraft by a Picture

- Negative Love

- The Good Morrow

- Love’s Infiniteness

- Satire 3

- Good Friday 1613, Riding Westward

- The Flea

- Funeral Elegy on Himself

- Elegy – The Autumnal

- Holy Sonnet – Oh, to vex me, contraries meet in one

- The Dissolution

- Love’s Alchemy

- The Prohibition

- Holy Sonnet – Thou has made me

- A Nocturnal Upon St Lucy’s Day, being the shortest day

- Love’s Diet

- The Relic

- The Ecstasy

- A Hymn to God the Father

Reviews

The best readers of poetry don’t recite it; they enact it, taking on the character of the narrator. The poetry of Metaphysical poet John Donne – once ranked with the works of Shakespeare and Milton – has at least two facets, so it’s fitting that this production has two narrators. Geoffrey Whitehead brings out the passion of Donne’s religious poetry, particularly the selections from the Holy Sonnets, and Will Keen specializes in the poems about love and sensuality. The two voices are very different, echoing the dualism that is one of Donne’s hallmarks. Both men remind us of the intense feeling that underlies the formalism of seventeenth-century English poetry at its best.

D.M.H., AudioFile

Booklet Notes

John Donne is one of the finest of all English poets. But he is still regarded as a difficult writer, convoluted, and requiring a greater level of application than almost any other. It is rather disarming, therefore, to discover that his contemporary reputation was based not just on his learning, cleverness and wit (though these were recognised as being of the foremost) but on his directness, harshness and lack of suavity. It was the personal nature of his poems that made him stand out from the filigree courtly versifiers of the time. Given the ravages endured in his personal life, it is evidence of the greatness of his mind that he could turn tragedy, persecution, conversion, ruin, despair and more into verses that are so stimulating and satisfying, brilliant and moving.

His father – who died suddenly when Donne was about four – was a successful ironmonger, and his mother was a daughter of the playwright John Heywood. They were also Catholics. This last is crucial, not just because it was Donne’s faith, but because the England in which he grew up was still heaving under the religious, political and social turmoil that was a legacy of the English Church’s split from Rome. Although Donne was born when Elizabeth I had reigned for 14 years and had managed to restore general security, there was still a dangerous stigma to being a Catholic. Donne knew this well – members of his own family had been (and were still) executed, imprisoned and exiled for their faith. Despite the risks, Donne was educated privately by the Jesuits and went on to both Oxford and Cambridge Universities. He was at each university for three years, but failed to graduate because he refused to swear the Oath of Supremacy, which accorded the monarch (rather than the Pope) supreme rule over the Church in England.

Was he a careerist

who dropped his

religion for

advancement or

a man agonised

by uncertainty?

Despite this refusal he studied for the law in London and spent his inheritance on the pleasures attendant on being one of the first men of his age. This was quite an ambition in the London of the time (Shakespeare, Raleigh, Drake, Jonson, Bacon and others were already filling the available spaces), but Donne was seen as the man who was arriving, with the personality to match: wise, attractive, witty, pointed, intelligent, knowing – and questioning. He had begun to examine his faith in the early 1590s, and was part of the army that fought the Spanish in 1597 and 1598, something he could hardly have undertaken if he felt bound to Rome. On his return he became the secretary to Sir Thomas Egerton, and it looked as though his career, freed from the constraints of avowed Catholicism, was about to start in earnest. And then it all crashed down around him.

In 1601 he secretly married Anne More, Sir Thomas’s niece. Once discovered, this roused the fury of her father Sir George More as well as Donne’s employer. They managed to get Donne not just sacked and disgraced but imprisoned (albeit briefly). Donne’s status and potential seemed ruined. ‘John Donne, Anne Donne, Un-done,’ he wrote to Anne.

For the best part of a decade he lived a life of shadowy uncertainty, on the farthest fringes of the Court in search of preferment, serving any patrons in whatever capacity he could, often only just managing to keep his family fed. This was unsurprising given the rate at which it grew; he and Anne had 12 children (although two were stillborn). But the number of people dependent on him, quite apart from the depth of his own concerns, weighed so heavily that he considered suicide.

The personal concerns ranged from the immediate (money) to the temporal (career) and the eternal (his relationship to God) – each of them seeming to affect him with equal intensity. All this was eased when Donne was effectively instructed by King James I of England and King James VI of Scotland to take Holy Orders and become an Anglican priest. Donne had maintained what contact with the Court he could, and had written polemics against aspects of Catholicism. James was not prepared to welcome him back into the heart of the Court itself, but the Church was at least rewarding both financially and spiritually. He was initially appointed a Royal Chaplain, eventually rising to Dean of St Paul’s, delivering sermons that were as famous as his poetry was to become. But just three years after his return to the warmth of social acceptance, Anne died giving birth. Hers was not the only death that hit him profoundly (close friends, patrons and three children under 10 also died), but, allied to his own frequent illnesses and abrupt changes in fortune, this bereavement contributed to a bitter despondency that fuels much of his later work. He never remarried.

He had been writing for most of his adult life, but largely for private circulation – as was common at the time. Some poems had made it beyond the hand-to-hand manuscript variety, but these were for public occasions such as those marking an event in a patron’s life. In general, his work was private; secret, even. He would not be published until after his death, and dating of his poems is therefore an approximate business (this volume is very broadly chronological). Coming to any conclusions about Donne himself and what he actually felt is equally hazardous. Critics have been shouting themselves hoarse for centuries with completely opposed opinions over exactly where to put him. He is most often placed with writers like George Herbert, Andrew Marvell and Thomas Carew under the grouping of The Metaphysical Poets, a label about as useful as The Brown-Haired Poets, and originally coined by Samuel Johnson as a deprecating nickname. There is some familiarity between these writers – neatness of conceits, determined concision (which can lead to a certain muddy density), conceptual complexity – but the label is unfortunate and over-simple, as almost all such labels must be.

Donne is too multifarious for that limitation. Was he a careerist who dropped his religion for advancement or a man agonised by uncertainty? Are his poems born from felt experience or intellectual pleasure in invention? Where did he really stand in love, politics, faith? He refuses to answer these questions simply because they are not simple issues. In one poem (A Nocturnal upon St Lucy’s Day) he considers the shortest day of the year and, in a punning extension, his relationship with a much-loved patroness called Lucy who had recently died. This becomes a more general examination of the nature of loss and the meaning of death, and his taut and unswerving intelligence manages to bind these ideas without it appearing contrived. The result is a dark meditation that carries in its beautiful wake a bleak consideration of mortality and sin. Similarly, in Good Friday 1613, Riding Westward, Donne works through the implications of a cornerstone of his faith but still manages to frame the issue with poetic and linguistic flourishes that illuminate the complexities he is trying to disentangle. Even his overtly erotic poetry contains intriguing contrarieties and ambivalences – just as the man did.

Donne was at once cynical, worldly, passionate and sexual; and devout, tortured and deeply challenged by the great religious rifts of his time. He was passionate about his lovers, about his relationship with God, about his work, about death. He was philosophical yet witty, playful yet darkly intense; and he made the form fit the function in poetry that is brilliantly opaque. Rather than diminish the work with easy rhythms and sentimental flourishes, he conflates ranges of images and ideas, searching the soul as well as the heart, seeing with the mind as well as the eye.

Notes by Roy McMillan