Audio Sample

William Shakespeare

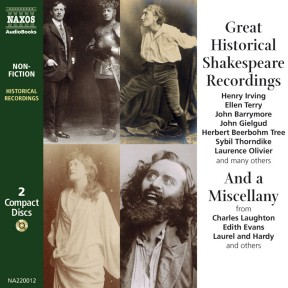

Great Historical Shakespeare Recordings

Performed by Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Arthur Bourchier, Lewis Waller, Frank Benson, Johnston Forbes Robertson, Sir John Gielgud, Sybil Thorndike, Lewis Casson, John Barrymore, Laurence Olivier, Henry Irving, Edwin Booth, Ellen Terry, Noel Coward, Gertrude Lawrence, Fred Terry, Julia Neilson, Henry Ainley, Bransby Williams, Edith Evans, Charles Laughton, Laurel and Hardy, Sarah Bernhardt, Jean Mounet-Sully, Constant Coquelin, Feodor Chaliapin & Alexander Moissi

selections

Historical recordings of actors from the beginning of the recording era. CD 1: Historical Shakespeare performances by Ainley, John Barrymore, Bourchier, Casson, Forbes-Robertson, John Geilgud (1920s and 1940s). CD 2: A miscellany. Some startling historical performances in a wide range of works from Edith Evans, Charles Laughton, Noel Coward, Sarah Bernhardt, Fred Terry, Laurel and Hardy, Edwin Booth, Bransby Williams, Jean Cocteau, Feodor Chaliapin and others.

-

2 CDs

Running Time: 2 h 06 m

More product details

ISBN: 978-962-634-200-8 Digital ISBN: 978-962-954-696-0 Cat. no.: NA220012 Download size: 30 MB Produced by: Nicolas Soames Compiled by: David Timson BISAC: DRA010000 Released: June 2000 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Cast

Herbert Beerbohm Tree as Mark Antony in JULIUS CAESAR Act III Scene 1

Herbert Beerbohm Tree as Falstaff in HENRY IV PART 1 Act V Scene 1

Arthur Bourchier as Macbeth in MACBETH Act II

Lewis Waller as Henry V in HENRY V Act III Scene 1

Frank Benson as Henry V in HENRY V Act III Scene 1

Johnston Forbes Robertson as Hamlet in HAMLET

Johnston Forbes Robertson as Hamlet in HAMLET

John Gielgud as Hamlet in HAMLET Act IV Scene 4

John Gielgud as Richard II in RICHARD II Act III

Sybil Thorndike and Lewis Casson in MACBETH Act I Scene 5

John Barrymore as Gloster in HENRY VI Part 3

John Barrymore as Hamlet in HAMLET Act III Scene 1

Laurence Olivier as Hamlet in HAMLET Act I Scene 2

Laurence Olivier as Henry V in HENRY V Act III Scene 1

Henry Irving as Richard III in RICHARD III Act I Scene 1

Henry Irving as Cardinal Wolsey in HENRY VIII Act III Scene 2

Edwin Booth as Othello in OTHELLO Act I Scene 3

Ellen Terry as Ophelia in HAMLET Act IV Scene 5

Ellen Terry as Juliet in ROMEO AND JULIET Act IV cene 3 ‘Good night. Get thee to bed and rest…’

Also includes:

Ellen Terry as Portia in THE MERCHANT OF VENICE Act IV Scene 1

Noel Coward and Gertrude Lawrence from Act I PRIVATE LIVES (Coward)

Fred Terry and Julia Neilson in THE SCARLET PIMPERNEL (Orczy)

Herbert Beerbohm Tree as Svengali in TRILBY(du Maurier)

Henry Ainley reads THE CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE (Tennyson)

Bransby Williams as Irving in THE BELLS

John Gielgud and Edith Evans in THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST (Wilde)

Charles Laughton reads THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS

Laurel and Hardy

Bransby Williams as The Stage Doorkeeper

Sarah Bernhardt as Phèdre PHEDRE (Racine)

Jean Mounet-Sully as Oedipus OEDIPUS (Sophocles)

Constant Coquelin as Cyrano from CYRANO DE BERGERAC

Feodor Chaliapin reads REVERIE (Nadson)

Alexander Moissi reads ERLKOENIG (Goethe)

Alexander Moissi in FAUST (Goethe)

Reviews

Naxos offers many excellent recordings of the Bard, but the breathtaking array of legendary performers – from Sarah Bernhardt to Laurel and Hardy to John Gielgud – makes this title, which includes performances from the beginning of the recording era, very special.

Library Journal

Winner of AudioFile Earphones Award

Despite hit-and-miss restoration, this is a delight for the theatre buff, cultural historian and acting professional. The first cassette includes speeches from Shakespeare recorded from 1896 to the 1940s, recited by the most notable actors of the day – Sir Henry Irving, the greatest of the Victorian actor-managers; Ellen Terry, his leading lady; a very young Gielgud; Olivier; Dame Sybil Thorndyke; the American Edwin Booth, John Wilkes’s brother; and the Great Profile, John Barrymore; among others. The second cassette presents a miscellaneous collection of theatre and vaudeville – notably Noel Coward and Gertrude Lawrence (the first Anna in The King and I) in the former’s musical comedy Private Lives; Coquelin, the original stage Cyrano, reading from that play in French; a turn by Laurel and Hardy; and the legendary Sarah Bernhardt. Obviously, some of these performances will seem overblown and dated, but others still possess considerable power. Naxos has spaced its signature classical music bridges to give the ear a rest from the often scratchy recordings, which have been lifted from old discs, wax cylinders, movie sound tracks and radio broadcasts.

Y.R., AudioFile

Booklet Notes

‘Life’s but a walking shadow

A poor player that struts and frets His hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more.’

With the development of Edison’s phono- graph in the 1880s, the ephemeral art of the actor found a little more permanence. Never again would a famous actor after his death be ‘heard no more’, and future generations would be able to judge for themselves whether his reputation was justified.

Since the 17th century, a classical actor’s reputation has stood or fallen by his interpretation of Shakespeare, so this first disc looks at the changing styles of Shakespearian acting from the beginning of recorded sound in the 1880s, to the late 1940s.

If only we could have heard the voice of Richard Burbage, the first great performer of Hamlet, or hear for ourselves whether Garrick spoke Shakespeare with his native Lichfield accent. Fortunately, recordings have survived of the greatest actor of the Victorian age, Sir Henry Irving.

In 1888, the personal representative of Edison, Colonel Gouraud, came to England with a prototype of the new phonograph, and publicised his employer’s new invention by recording some of the most eminent figures in English society. After a dinner party at the Colonel’s, Irving was requested to recite something, but he was nervous and, as his host said, ‘frightened out of his voice’. Nevertheless he appeared to be intrigued by this ‘most extraordinary instrument phenomenon’. He wrote to Ellen Terry: ‘You speak into it and everything is recorded, voice, tone, intonation, everything. You turn a little wheel, and forth it comes, and can be repeated ten thousands of times. Only fancy what this suggests’.

Eventually, Irving mastered the new technique of directing his voice down a speaking-tube, which caused a needle, attached to a diaphragm, to vibrate and leave an impression of sound-waves on a wax cylinder. The needle then retraced its journey through the grooves, playing back the recording through a large conically- shaped horn. The bigger the horn, the louder the sound.

Sir Henry was not over-impressed with the result: ‘Is that my voice? My God!’ The phonograph was hardly more than a drawing-room entertainment at this stage, and some years away from commercial development, so the survival of the recordings of Irving included here is little short of a miracle. These early cylinders are important historic documents which, due to the limitations of the technology give us just an impression of Irving, Terry and the American Edwin Booth – which is why they have been placed at the end of the CD.

The first is a speech from Richard III [track 15] which Irving first played at the Lyceum in 1877. As one observer said: ‘he never lost nobility, the nobility of Lucifer’. Irving revived Richard III in 1896, which is probably when this recording was made.

The second [track 16] is a recording of Wolsey‘s speech in Henry VIII, which Irving played in 1892. He seems more at his ease in this recording, leading some scholars to doubt whether this is in fact Irving at all, or one of his many imitators. For me, the inclusion of a line not written by Shakespeare at the end of the speech makes itauthentic.ItisanextralineaddedbyIrving to cover the dying Cardinal’s well- documented exit across the Lyceum stage: ‘Come Cromwell, let us go in. My spirit is broken, – Ah!’ He also adds a postscript, saying ‘I consider that one of the finest tragedies in Shakespeare.’

Irving’s idiosyncratic pronunciation was much commented upon by his contemporaries. He pronounced ‘dog’ as ‘dug’, and famously in The Bells, said ‘Tack the rup from mey nek’ (‘Take the rope from my neck’). These peculiarities are evident in these recordings. For instance, in Richard III he says ‘Sun of Yark’, for ‘Sun of York.’ Irving was well aware of his deficiencies. He himself had corrected a bad stammer he had had since a boy, and to make the most of his thin voice he made use of nasal resonance. But it was not vocal power that made Irving a great actor; it was his gift of being able to hold an audience by the force of his magnetic personality. We can only catch a glimpse of his talent through these rather primitive recordings.

In the United States of America, the great Shakespearian tragedian, and Irving’s was Edwin Booth (1833- from a theatrical family that with real-life tragedy. His Brutus Booth, had suffered insanity, and Edwin’s brother, John Wilkes Booth, assassinated Abraham Lincoln in 1865. This event cast a shadow over the rest of Edwin’s life and career. In contemporary, 93). He came was blighted father, Junius from bouts of 1882 Irving invited Booth to play Othello in London, opposite his Iago. Booth’s Othello was described by his biographer William Winter as ‘affluent with feeling, eloquent, picturesque, and admirable for sustained power and symmetry.’ In 1890 Booth made a private recording of Othello’s speech to the Senate, for his wife, which is full of quiet dignity [track 17]. Does one detect in the restrained and almost naturalistic delivery the beginnings of an understanding and sensitivity towards the new technology?

Irving’s stage partner at the Lyceum from 1878 to 1896 was Ellen Terry (1847-1928), and no actress was more loved by her followers. She was intensely feminine and the embodiment of Shakespeare’s heroines. As one reviewer said, ‘it was as if she had met, and talked with, and lived with them all.’ After leaving the stage, she toured extensively with her lecture-recital on Shakespeare’s Heroines, and was persuaded, whilst in America in 1911, to make the recordings included here. Astonishingly she was 63 at the time, but her youthful energy, which she never seems to have lost, is still in evidence, giving us a taste of those performances with Irving of more than thirty years earlier.

In preparing for her Ophelia, [track 18] which she first played in 1878, she studied lunatics in an asylum: ‘I noticed a young girl gazing at the wall. I went between her and the wall to see her face. It was quite vacant, but the body expressed that she was waiting, waiting. Suddenly she threw up her hands and sped across the room like a swallow. I never forgot it: the movement was as poignant as it was beautiful.’ Ellen Terry did not think her Juliet, [track 19] which she first played in 1882, was a success, lacking, she said, ‘original impulse’. But Irving admired it and her recording of the Potion scene is compelling. Her Portia, from The Merchant of Venice [track 20] which she had played as early as 1875, was ‘a perfect woman, in all the attributes that fascinate’, yet in the trial scene Ellen invested her ‘with that fine light of celestial anger – that momentary thrill of moral austerity’ (William Winter). Her last performance with Irving, in 1902, was in the role of Portia.

After the death of Irving in 1905, the mantle of Shakespearian production fell to Herbert Beerbohm Tree (1853-1917). Between the late 1890s and 1917 he mounted sixteen lavish Shakespearian productions at his own theatre, Her Majesty’s. Tree was something of an idealist and a dreamer, and was lacking in self-discipline as an actor. This did not make him really suitable for playing Shakespeare, particularly passionate or heroic parts. His talent was as a character actor, and using his considerable skills of make-up, he was able to create bizarre and eccentric characters which were his greatest successes. (As an example, hear his Svengali on track 4).

In 1898, he mounted an epic production of Julius Caesar, with sets by Alma Tadema, and large, carefully choreographed, crowd scenes. In choosing which part to play he wrote: ‘For the scholar, Brutus, for the actor, Cassius, for the public, Antony.’ He chose the public. Not having had any vocal training, Tree found difficulty in sustaining the verse and reaching a rhetorical climax. Perhaps this is why his recording of Antony’s speech over Caesar’s body [track 1], made in 1906, feels as if it’s on the edge of being sung. It is constructed like an aria, each line moving up a semitone until the climax is reached. It sounds odd to our ears, and a far cry from modern Shakespearian performing styles, yet, given the size of the theatre he had to fill, this grandiose, unnaturalistic style would have been very thrilling.

In the second recording, Tree is much more at home with his broad and rich characterisation of Falstaff [track 2].

The disciples of Irving and Tree who made early recordings included Arthur Bourchier, Lewis Waller, Frank Benson and Johnston Forbes-Robertson.

Arthur Bourchier (1863-1927), was an enthusiast for Shakespeare. His acting is full of ardour and energy, broad brushstrokes, with little space for subtlety and delicacy. He was an aggressive actor-manager, who championed contemporary playwrights like Pinero and Jones. His performance as Macbeth, here recorded in 1909 [track 3] was described by one reviewer as ‘merely a bluff and rugged warrior’. Nevertheless, I think he probably represents the most usual style of playing Shakespeare at the turn of the century.

The good looks of Lewis Waller (1860- 1915), soon established him as a matinee idol, and he was renowned for playing romantic parts. Thousands of postcards were published for his adoring female fans, who banded themselves together into a society called ‘Keen On Waller’. They wore button- hole badges displaying they were ‘K.O.W.s’ – which caused much mirthful comment in the popular press of the day!

Waller starred as Henry V in 1901, [track 4] when his ‘ringing voice and striking presence’ made it a popular success. J.T. Grein wrote of his performance: ‘He quivers with passion, with excitement, with righteous ardour that we in our seats begin to feel the effect.’ A century later we can still share in that experience.

Sir Frank Benson (1858-1939), an Oxford graduate and Shakespeare scholar, was also a keen sportsman, and his approach to Shakespeare is redolent of the playing field. Max Beerbohm wickedly reviewed his production of Henry V [track 5] in 1900 in this vein: ‘The fielding was excellent, and so was the batting. Speech after speech was sent spinning across the boundary.’

Nevertheless, Benson and his ‘team’ toured Shakespeare unceasingly throughout Britain and its Empire from the 1890s through to the 1930s, giving generations their first experience of the plays.

Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson (1853- 1937) possessed great physical beauty, a scholarly mind and in his heyday a voice ‘of gold and silver tones’. Fine attributes for an actor, but Forbes-Robertson, despite his success, never really cared for acting. In 1913 he was a popular Hamlet, described by one reviewer as being ‘patient and careful, the temperament of an English gentleman’, and George Bernard Shaw said his performance showed ‘a genuine delight in Shakespeare’s art and a natural familiarity with the plane of his imagination’. It is this delight and familiarity that comes across in his recorded lecture on Hamlet made in 1928 [tracks 6 and 7]. His delivery is more in keeping with modern approaches to Shakespearian acting, relaxed and naturalistic, less rhetorical.

His approach sounds distinctly more modern than the early recording of Hamlet by John Gielgud (1904-2000) [track 8] which seems to be overshadowed by the nineteenth-century acting tradition which was his background; Ellen Terry was his great aunt. Similarly, his sense of rhetoric and poetry dominates his performance of Richard II [track 9], sometimes at the expense of naturalism.

To be fair, Gielgud of course spanned the twentieth century, and these are early attempts at roles he was to make his own. He was only 23 when he made the Richard II recording in 1927. A later recording made in the 1950s is exemplary. The comparison between Forbes-Robertson and Gielgud shows that a particular acting style does not necessarily belong to one generation.

Sybil Thorndike (1882-1976) and her husband Lewis Casson (1875-1969) were stalwarts of the Old Vic in the early years of the twentieth century, then under the management of the eccentric Lilian Baylis. Her aim was to make Shakespeare popular for ordinary working people. She greatly encouraged a new generation of actors to join her company. Her recruits, John Gielgud, Edith Evans, Sybil Thorndike and Lewis Casson, were of the new school of Shakespearian acting promoted by William Poel and taught by Ben Greet. Poel desired to sweep away all the accretions of the nineteenth century and get back to a faster, more immediate style of verse-speaking. This recording from 1930, of Thorndike and Casson in Macbeth [track 10], well illustrates the changing tempo of performance.

With the advent of electrical recording in the 1920s, where a microphone was first used and the volume could be controlled by an amplifier, the quality of reproduction significantly improves, and the style of acting begins to adapt to this more sophisticated advance. Hitherto little concession had been made by the actors to the recording process. The breadth and size of their performances did not change significantly from the theatre to the studio.

An actor perfectly at ease with the medium and using it to enhance and increase the effectiveness of his performance was John Barrymore (1882-1942). Like Edwin Booth he belonged to a theatrical dynasty, and some critics think he could have been as great a Shakespearian actor as Booth. He was a sensational Hamlet in 1922 on both sides of the Atlantic, but turned instead to Hollywood, becoming a matinée idol. The ease and confidentiality of his delivery in the speech from Henry VI [track 11] show his experience in the subtle world of the film. The speech from Hamlet [track 12], made as a ‘promotion’ towards the end of his life, may show some vocal signs of his fast lifestyle, but his natural and intelligent delivery also makes us think of the fascinating Shakespearian actor he might have been.

An actor who was both a film and a Shakespearian actor, and occasionally managed to combine both, was Laurence Olivier (1907-1989). The excerpt here from the film soundtrack of Hamlet (1948) [track 13] shows how far sound recording had progressed in 60 years. The high quality of the sound recording allows Olivier to take us right into the mind of Hamlet, he seems to be just thinking rather than speaking the lines.

By contrast, the Harfleur speech from his film of Henry V (1944) [track 14] is boldly theatrical. It is a trumpet call to arms at a time of national conflict, and in its style unashamedly takes us back to the ‘ringing voice’ of Lewis Waller [track 4].

These early recordings show us how the art of acting Shakespeare, which had been handed on from generation to generation, was changed and refined by the invention of recorded sound. As the twentieth century progressed, the larger style gave way to a more subtle and internalised style, matching the techniques required for those two other technological revolutions of the last century, film and television. These changes have ensured that Shakespeare has not remained solely the prerogative of the theatre, but has reached an ever-increasing audience in the electronic age.

Our second CD shows how the rapidly developing medium of recorded sound caught the popular imagination in the early years of the twentieth century. Jazz bands, brass bands, music-hall artists, politicians, all rushed to get themselves on record, and actors were not far behind. Noel Coward (1899-1973) was always a successful self- publicist and soon realised that recorded excerpts from his plays would considerably help the box office. The excerpts here from Private Lives [tracks 1 and 2] recorded in 1930, with the Master and the sparkling Gertrude Lawrence (1898-1952), capture forever the spirit and style of the theatre in the 1920s.

An earlier popular theatrical duo were Fred Terry (1863-1933) and his wife Julia Neilson (1868-1957) who recorded their ‘hit’ The Scarlet Pimpernel in 1906 [track 3]. As A.E. Wilson said, ‘A handsomer pair of lovers never trod the boards or raised rubbish to the plane of pure delight.’ Rubbish or not, it was successfully revived throughout their long careers.

Herbert Beerbohm Tree (1853-1917), as we have already seen, had a huge success, mounting epic productions of Shakespeare, but his greatest triumph came with the adaptation of Du Maurier’s novel Trilby, which he first produced in 1895.

A character actor of considerable scope, with the aid of his artistry in greasepaint, he brilliantly personified the evil Svengali [track 4]. He brought Du Maurier’s drawings to life. A.E. Wilson described his performance as having ‘the air of romantic shabbiness and picturesque grime with guttural alien accent – the very tones of which struck a chill.’ He recorded this excerpt in 1906.

There was a growing public for the theatre in the early 1900s. It was the heyday of the picture postcard and fans competed to collect whole sets of their favourites. The recording companies too saw the potential in persuading the stars to record their party pieces. One of the most beautiful and adored actors of his generation was Henry Ainley (1879-1945) who also had a musical voice ranging ‘from fluty sweetness to deep organ tone’. Here he reads Tennyson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade [track 5].

Giving ‘impressions’ of famous people is nothing new, and Bransby Williams (1870- 1961) had a long and successful career as a ‘mimic’ (his term) in the music-hall. Over sixty years in fact. The arrival of recorded sound was a boon to the impersonator and Williams’ celebrated imitation of Irving in The Bells [track 6] has led some to question the authenticity of the Irving recordings (see CD 1). He captures Irving’s vocal mannerisms to perfection, and it is not perhaps surprising to learn that Irving was ‘sensitive’ about his impersonators, of whom there were many. On one occasion, he called on the power of the Lord Chamberlain to threaten the withdrawal of the offending theatre’s licence. Bransby Williams seems to have escaped unscathed, and recorded the extract included here around 1914. He was still performing it in his eightieth year, 1950, on another piece of new technology – the television.

Edith Evans (1888-1976) will always be associated with The Importance of Being Earnest in which she gave the definitive performance of Lady Bracknell. The ‘handbag’ line must be the most imitated piece of theatre in the Western world! But the performance she gave in John Gielgud’s 1939 production was one of subtlety and detail: ‘I know those sort of women,’ she said, ‘they ring the bell and tell you to put a lump of coal on the fire; they spoke meticulously, they were all very good-looking and didn’t have any nerves’. Here she recreates her performance with her director John Gielgud, himself the very incarnation of John Worthing [track 7].

Charles Laughton (1899-1962) was one of scores of British actors who made his name in Hollywood. Like Stan Laurel, he came to prefer the American way of life, and scored a popular hit in the film Ruggles of Red Gap (1935), where he played an English butler incongruously working in the Wild West. During the course of the action Ruggles, the butler, recites Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address to great effect. It is a fine speech and this recording, made in 1937, shows Laughton at his best [track 8]. Towards the end of his life, he made more use of his rhetorical skills and turned increasingly to the recital platform with readings from The Bible and Dickens.

Recording companies were always looking for novelties, and music-hall artists performing sketches and monologues were very popular in the first half of the twentieth century. Many comic moments from the films of Laurel and Hardy for instance were transcribed to disc. The recording included here [track 9], though, was made to promote one of their far too infrequent visits to Britain. It is a curious paradox to think that these two stars, who made their name in films without sound, could be so successful in sound without vision. It is a fine example of two geniuses adapting their skills to the now well-established medium of sound recording.

We end the English section with another ‘novelty act’ by Bransby Williams. Throughout his long career, The Stage Doorkeeper [track 10] was one of his most popular ‘turns’. In it, he mimicked the most successful performers of the day, continually changing them to remain topical.

Here, frozen in time, are the ‘voices’ of the performers of the moment in 1914, the year of the recording. George Alexander, the actor-manager, Forbes Robertson as Hamlet, and the music-hall artists Chirgwin, ‘the White-Eyed Kaffir’; G.P. Huntley, the silly ass type; R.G. Knowles, the eccentric comedian; Fred Emney and George Formby (senior) with his characteristic cough. Many of these names, now long forgotten by the public, were never recorded themselves, and it is poignant to hear them one step removed as it were. It makes one grateful that so many early recordings have survived of the great artists of yesterday, and I hope this compilation will help to bring those ‘poor players’ out of the ‘shadows’ and once more into the light.

Recording companies on the continent were also eager to preserve for posterity the leading actors of their day. Most famous and most notorious was the great Sarah Bernhardt ( 1845-1923). Ellen Terry said of her: ‘She was as transparent as an azalea – like a cloud, only not so thick. Smoke from a burning paper describes her more nearly! She was hollow-eyed, thin, almost consumptive-looking. Her body was not the prison of her soul, but its shadow – she always seemed to me more a symbol, an ideal, an epitome than a woman – which makes her so easy in such lofty parts as Phèdre.’ Her voice was variously described as a ‘golden bell’, or the ‘silver sound of running water’. Its sustained power in this extract from Racine’s Phèdre recorded in 1903 is thrilling [track 11].

Two of her leading men are also featured here. Jean Mounet-Sully (1841-1916) was a major tragic actor of the nineteenth century whose passion, conviction and sheer dramatic power overwhelmed his audiences. He played opposite Bernhardt in Hernani by Victor Hugo, but he was a renowned Oedipus, recorded here in 1912 [track 12].

Constant Coquelin (1841-1909) was essentially a comic actor making his debut at the Comédie-Française. He joined Sarah Bernhardt’s company in 1892, but his strong personality clashed with hers and their association was short-lived. He will always be known as the originator of Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac, which he played over 400 times [track 13].

The Russian bass, Feodor Chaliapin (1873-1938), was a formidable talent. He was a great singer and also a great actor. On stage he blended the two arts. His voice ‘rolled out like melodious thunder’ and could be at once ‘powerful and caressing’. He left the Soviet Union in 1921, and became an international artist. In 1922, he was recorded performing Reverie by Nadson [track 14].

Alexander Moissi (1880-1935), although of Italian/Albanian parentage, became a leading German actor from 1905, working with the innovative Max Reinhardt in Berlin. He was a notable proponent of the title role of Goethe’s Faust [track 15], recorded here in 1927, and in 1930 came to London with his version of Hamlet. Goethe’s Erlkoenig [track 16] was famously set by Schubert. Both the recordings here show us his rich and musical speaking voice.

Notes by David Timson