Audio Sample

Leo Tolstoy

The Kreutzer Sonata

Read by Jonathan Oliver

unabridged

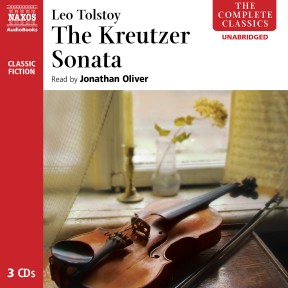

One of Tolstoy’s most important shorter works, The Kreutzer Sonata presents a problematic view of the relationship between the sexes and promotes abstinence as the solution. Pozdnyshev jealously observes the intimacy that emerges between his wife and a violin player. Haunted by ‘The Kreutzer Sonata’ over which they bonded; it plays round and round in Pozdnyshev’s head driving him to distraction and to an unquenchable rage. The Kreutzer Sonata is a psychologically fascinating novella, offering interesting insights into the power play between the sexes.

-

3 CDs

Running Time: 3 h 56 m

More product details

ISBN: 978-1-84379-356-4 Digital ISBN: 978-962-954-963-3 Cat. no.: NA335612 Download size: 57 MB BISAC: FIC004000 Released: June 2010 -

Listen to this title at Audible.com↗Listen to this title at the Naxos Spoken Word Library↗

Due to copyright, this title is not currently available in your region.

You May Also Enjoy

Reviews

This grim classic is told by Pozdnyshev to a fellow passenger, both of whom are traveling on a train in Russia. Pozdnyshev has murdered his wife and is telling the story of how the evolution of his beliefs led him to this horrible event. His lengthy argument, in his own defense, boils down to his belief that sex is a corrupting influence and therefore should be eschewed by all, thus leading to the end of mankind. He is disturbed and disturbing, mad with jealousy, cynical and angry. Stage actor and experienced narrator Jonathan Oliver’s interpretation is superb. Though this is mostly a monologue, he does voice the various characters that appear in the story. The author’s note at the end confirms that Tolstoy’s own beliefs closely parallel his main character. There are musical interludes with a violinist and pianist playing Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata (No. 9) which is totally appropriate. Why the decision was made to include music from Sonata No. 5 is puzzling.

Susan Rosenzweig, SoundCommentary.com

Booklet Notes

Leo Tolstoy holds a unique place in European – possibly world – literature. Many of his books have the unquestioned status of masterpieces, and in Russia he is revered as much as Shakespeare and Elgar are in Britain, or Goethe and Wagner in Germany, or Zola, Flaubert, Stendhal and Debussy combined in France. But he has a similar hold on the spiritual as well as the artistic heart and mind, making him almost a kind of Gandhi or Luther. This is not just in a metaphorical sense, and not just in terms of the fervour with which his devotees adored his writings and followed his actions; in the later years of his life he became a figurehead for a new kind of Christianity, and, having had his works banned by the secular authorities, he was excommunicated by the Church.

He cannot have been surprised – after all, he wanted to abolish governments and the Church altogether. He wrote against the prevailing orthodoxy (political and religious) in a largely totalitarian state, and it was only the extremely special regard in which he was held by the public that stopped him from receiving harsher penalties than bans. He took up the cause of passive resistance to evil, and would be an influence on Gandhi when the latter decided to adopt a non-violent approach in his attempt to gain independence for India. Tolstoy’s beginnings, however, were starkly different from the ascetic conclusion.

He was born to the gentry, on the family estate, and educated privately before attending Kazan University. But even there he showed a displeasure at the way things were run and the courses were taught – and he left before graduating. He was well-read and intelligent, but was also in a position to enjoy considerable privilege, which he did. His remembrances of this dissolute time in his life later caused him profound distress and regret. His actions went far beyond youthful indiscretions or drink-fuelled gambling and debauchery; there were duels and even a suggestion of a murder.

Although he

would never

free himself

completely

from the

autobiographical

in his later

works, his

earliest were

quite

specifically

memoirs

It was a decision to travel with his brother to the Caucasus that appears to have triggered a greater moral sense. The countryside and especially the peasants and their way of life seemed to stir something profound in him. Warfare would, too. He joined the army and saw active service during the Crimean War. And a final shift in his thinking was inspired by trips to Europe in the late 1850s and early 60s. Apart from giving Tolstoy a sense of the world outside the repressive and inward-looking Russia of the time, his European experiences allowed some of Tolstoy’s angry views to crystallise, thanks to the sympathetic understanding of other European intellectuals and artists. He determined never to serve the State again, started to believe in the possibility of change through education (he went on to found an experimental school on his family’s lands), and began to write.

Although he would never free himself completely from the autobiographical in his later works, his earliest were quite specifically memoirs. They were not as comprehensive as his diaries, however. These he kept assiduously, and in a token of fervent honesty he showed them to his bride-to-be on the eve of their marriage. She discovered not merely that he had had considerable sexual experience before he met her, but that he had fathered a child by one of the serfs who still worked on his farm. Sonya dealt with that, however, and with much more besides. Their marriage, though it gave them 13 children, was deeply unhappy, despite the evident initial attraction. The honeymoon period lasted long enough for her to keep his business affairs under control, which involved managing his experimental schools and allowing him the freedom to write. The literary world owes Sonya an incalculable debt. While she was beside him, he wrote War and Peace and Anna Karenina. These two contain evidence of what were to become his later preoccupations – pacifism, the corrupting capacity of government, the foolhardy conventions that stifle people, and the dead hand of dogma that kills mankind’s relationship with God.

These themes become more and more explicit towards the end of Anna Karenina, the theological one in particular. When he had finished Anna Karenina, Tolstoy began to shift away from the novel as a narrative form, and wrote shorter fiction, essays, pamphlets, parables, and tracts on art and religion. His shorter work also became more directly a reflection of his personal beliefs. The Devil, Father Sergius, How Much Land Does a Man Need?, The Death of Ivan Ilyich and The Kreutzer Sonata were all written as a means of illustrating Tolstoy’s shift towards a more fundamental theology, which included an ascetic of self-denial. This did not stop people from misreading The Kreutzer Sonata, and seeing it as a call for freedom from restraint. In it, the central character, Pozdnyshev, is travelling on a train when he overhears a conversation about love, marriage and divorce. He joins the conversation, and is startlingly frank about how his initial love for his wife turned to a bitter mix of desire and hatred; how women’s dresses arouse men’s lust; and how music can inflame people’s passions, even so much as to change their nature. This is a matter that touches him deeply, since his wife met a violinist with whom she would play Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata, and Pozdnyshev becomes ragingly jealous. The opposing forces of his carnality and his desire for moral behaviour eventually drive Pozdnyshev to an act of explosive violence, for which he is seeking a kind of atonement.

Chekhov recognised the artistic strengths of The Kreutzer Sonata; but Theodore Roosevelt didn’t – he said it ‘could only have been written by a man of a diseased moral nature’ – and the book was banned in certain states in America. There is a powerful irony in the idea of Tolstoy – who was trying to re-establish a purer connection between God and Man – being chastised as a degenerate by the Russian Church, by the Tsarist autocracy, and by the democratic free-for-allers of America all at the same time. While The Kreutzer Sonata seems extreme in its expression of disgust at the nature of sex, and the furies it unleashes on marriage and lust, it still shows Tolstoy’s great strengths: his unbowed intensity of feeling and his grasp of what happens in people’s minds and hearts.

The last 10 or 15 years of his life saw an even greater determination to follow the principles he espoused, and even greater deterioration of relations with his family. He was disgusted with the sophistication and falsity of his early work, renounced possessions and money, and eventually (at the age of 82) left home with a daughter and his doctor to fulfil a long-held desire to become a wandering ascetic. A few days later at a railway station, he succumbed to suspected pneumonia, and died shortly afterwards, still refusing to see his wife. His home became a place of pilgrimage, and in a sense it still is; for anyone who loves literature must pay their respects to Tolstoy. It is not what he would have wanted – but then nothing ever was.

Notes by Roy McMillan